Multilingual Communication for Resilience

Sharon O’Brien, Associate Dean for Research – Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, Dublin City University

In a crisis or disaster, it is generally agreed and understood that timely, clear, and accurate communication is essential. It is not as clear that this communication needs to be in multiple languages and formats and delivered across many different channels. Our increasingly multilingual and multicultural societies demand a multilingual approach to crisis communication, and translation and interpreting play a crucial role.

Translation in Different Phases of Disaster

Suppose you ask people about how translation can contribute to crisis response. Their first thoughts usually turn to interpreting (i.e., oral translation) and the immediate aftermath of a crisis, such as an earthquake. Interpreting is indeed crucial in these first hours of response. As infrastructure and “standard services” can be seriously disrupted, it is also crucial that (written) translation is delivered through TV, websites, social media, etc. But, as disaster scholars argue (yes, there are such people!), disasters have multiple phases and can be cascading, where one event sets off various layers of crises that are protracted in nature. These phases are usually characterized as Response, Recovery, Mitigation, and Preparedness. The massive potential for translation in the phases beyond response is often overlooked.

Let’s take a look at “recovery” as an example. An earthquake regularly results in infrastructural damage. If your house is destroyed, you must find out the policy and procedures for claiming insurance for rebuilding your family’s home. Suppose that information, and the necessary forms, are in a language you either do not speak or struggle with. You are now faced with additional trauma and difficulty on top of what you have already endured. Translation is essential to ensure fair access to information. And, contrary to what some governments thought during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s not sufficient to machine translate that information and post it online without any human post-editing.

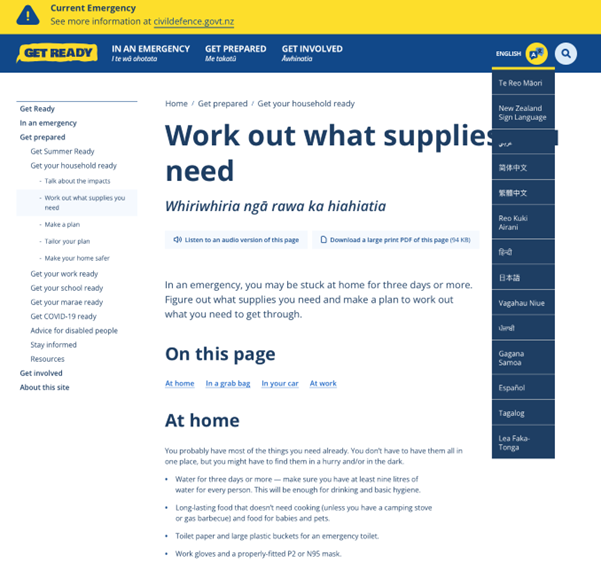

Preparedness refers to being as ready and resilient as possible during a crisis or disaster. If, for example, you are a refugee who recently arrived in a country such as New Zealand, you will need to know what a ‘Grab Bag’ is and how to prepare one in case of an earthquake. Grab Bag is a concept unfamiliar to those from countries where an earthquake is not a primary hazard. The advice on Grab Bags needs to be translated and communicated so that those who do not speak a region’s official or dominant languages can be equally resilient. New Zealand’s Civil Defence website shows they’ve taken this seriously, providing information in English, Te Reo Māori, and other languages highly relevant to that region.

National Emergency Response Policies

How does it come about that a government considers the language needs of its citizens in an emergency? Only a few governments have paid sufficient attention to this until the pandemic taught us all a lesson. People will remember the ‘no one is safe until everyone is’ line that was frequently cited during those crazy pandemic lockdown days. For everyone to be safe, we need equal access to information and services, which also requires quality translation. We also need foresight and leadership. We need our societies‘ multilingual and multicultural nature recognized and for multilingualism to be enshrined in national emergency response policies. EU-funded research we conducted at Dublin City University in collaboration with international partners demonstrated that governments had not given sufficient thought to the need for translation before, during, and after emergencies. This led to the development of ten crisis translation policy recommendations, which we continue to promote in the hope that they will be adopted by national and international authorities to increase society’s resilience to disasters.

Building on adopting these policies, we need to turn attention to their implementation. How do you measure an organization’s maturity to provide multilingualism in a crisis or disaster? We have also started to investigate this with a proposal for a first-ever crisis translation maturity model, which we are developing further in collaboration with various non-academic partners.

Training

Even if the need for translation in crisis settings is recognized, it is often the case that nobody in an organization with training in translation is able to provide the service. Humanitarian response organizations sometimes turn to multilingual staff for extra duties like translation and interpreting. Still, they need to be trained for these specialized tasks, which takes them away from the work they were hired for.

Using volunteers is a common practice, too; some may be trained in translation and interpreting, while others have yet to be trained. With this in mind, we created a YouTube Channel on Crisis Translation that offers an introductory, 101-type course on concepts of translation for anyone who needs access to it. Some of these mini-courses have been subtitled into multiple languages by students at DCU’s partner universities in Switzerland and Japan. These courses are, of course, no substitute for professional services, but it can be the case that there are very few trained language professionals for language pairs affected by disasters. Consequently, people turn to machine translation instead. Anyone who knows anything about MT knows this can be problematic, especially for low-resource languages, and especially when human health and well-being are at stake. Having good levels of MT literacy is, therefore, crucial.

Beyond Multilingualism

Communication in all phases of crises needs to go beyond ‘just’ language. Even if the information has been translated, culture plays an important role. As we saw during the pandemic, different nationalities behaved differently regarding vaccine uptake, even within the same country. Culture, trust of authority, and social media mis- and disinformation play a role here that is very difficult to untangle. Translation is a first step, but understanding culture and having direct access to the communities you want to communicate with is crucial. It’s also crucial to adopt a two-way communication protocol. In other words, it’s not enough to translate ‘for’; we must also figure out how to translate ‘with.’

We need to open our minds to other communities who need information, such as the deaf, hard of hearing, and blind, those with literacy issues, and older people who may not have the digital skills required to access information in our digital age. The challenge goes far beyond translating words from one language to another. It concerns accessibility and equality.

The Language Services Industry and Crisis Response

The good news is that academia, humanitarian responders, governmental organizations, and others are now realizing that broadly understood translation is a valuable and essential crisis communication tool that can contribute to a community’s resilience.

The language services industry is very well placed to take up this cause. Many have already donated to organizations like Clear Global, of course. Beyond that, the industry has offices in many corners of the world where local authorities could be lobbied to ensure that the multilingual needs of the community are enshrined in policy and practice for crisis response. The emphasis should lie on recovery, mitigation, and preparedness, not only in response. Pro bono professional linguistic services could be offered to translate content like the „Grab Bag“ information. Advice on how to use tools, technologies and how to manage translation in general and accessibility specifically could be offered. With my researcher’s hat on, there are co-funding collaboration opportunities, so please reach out!

Bio

Sharon O’Brien is a Professor of Translation Studies in the School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies at Dublin City University (DCU). Her research focuses on translation in crisis settings and machine translation. Previously, she worked as a translation technology consultant in the localization industry.