Linguistic Validation (LV) in Life Sciences: Overview and Best Practices

Anyone working in multinational clinical trials involving languages other than English will likely have heard the term “linguistic validation” more than a handful of times. But what, exactly, does it entail? Why is it important that certain types of content are not “just translated”?

In this first of two articles, we’ll explore LV, its steps, use cases, the regulatory landscape, and why it’s essential to plan and conduct LV projects carefully. A second article will focus on the pivotal role that language professionals and language service providers (LSPs) play in the process.

Defining Linguistic Validation

Generally, “linguistic validation” describes a complex, multi-step process used for specific types of content in the life sciences. Linguistic validation was developed to ensure that translations into other languages accurately reflect the original instrument’s concepts and are culturally appropriate and conceptually equivalent. LV involves various stakeholders with very specific linguistic and subject matter expertise, ranging from professional translators to reviewers, clinicians, and project managers.

Steps include concept clarification, forward and backward translation, reconciliation, and active testing of the translated text through clinician review and/or cognitive debriefing in the target population and language.

Stages of Linguistic Validation

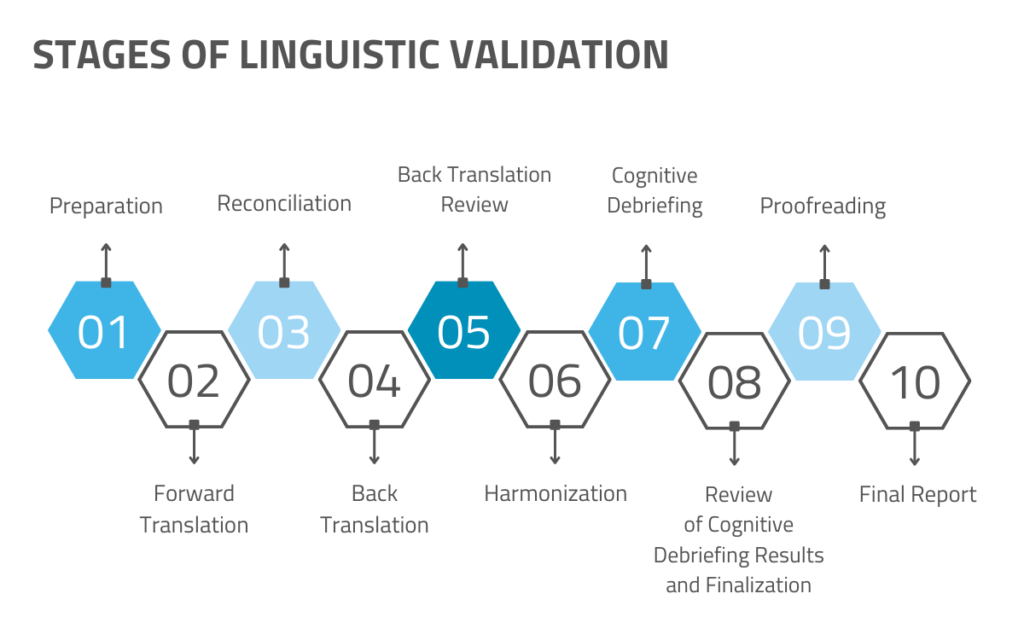

In a seminal paper published in 2010, the ISPOR task force proposed a 10-step process for the translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcomes (PRO), which is largely followed today. Steps include:

In practice, although there can be some variation, especially in terms of cognitive debriefing and/or clinician review, it generally looks something like this:

Step 1: Concept Definition

Process: The instrument/outcome measure is reviewed, and key concepts are defined.

Product: A comprehensive list and explanation of concepts used in the instrument to ensure cultural equivalency during the translation process. This list is later made available to all translators and stakeholders except the back-translator.

People: Instrument developers and project owners.

Step 2: Forward Translation (FT) x2

Process: Translations of the original instrument are elaborated by two translators working separately and without coordination.

Product: Two distinct versions of the original instrument in the target language.

People: Professional translators who are subject matter experts proficient in both the source and the target language and/or language variant(s).

Step 3: Reconciliation

Process: The two FTs are optimized and reconciled into one version.

Product: A single reconciled forward translation.

People: This step may involve professional translators, project managers, and other subject matter and linguistic experts.

Step 4: Backward Translation (BT)

Process: The reconciled version of the FT is translated back into the original language to assess accuracy. To ensure objectivity, the person performing the BT is not provided with the original instrument.

Product: A version of the original instrument translated from the reconciled FT back into the source language.

People: A third professional translator who is a subject matter expert proficient in both the source and the target language. To ensure objectivity, this cannot be one of the translators who did the FT.

Step 5: Review, Reconciliation, and Harmonization

Process: The BT is reviewed against the FT, and relevant changes are made in terms of linguistic accuracy, cultural validity, and clinical considerations. This process may be iterative, and arguments are generally provided to support any changes made during this stage.

Product: The preliminary final version of the original instrument in the target language.

People: Depending on the scale and content of the project, translators, linguistic consultants, and clinicians may be involved to varying degrees.

Step 6: Cognitive Debriefing (“Pilot Testing”)

Process: The translated instrument is “pilot-tested” with representatives of the target patient population who are native speakers of the target language. Through structured interviews, trained interviewers seek to determine whether patients interpret the questions and use response scales as intended and whether all relevant concepts are covered. Interviewees are often asked to explain their responses.

Product: A summary of results that will determine whether the instrument can be used as-is or requires alterations.

People: Trained interviewers who are fluent in the target language and interviewees.

Step 7: Finalization/Final Review

Process: The final version of the translated instrument after completion of the previous steps is approved, formatted, and proofread.

Product: The final version of the translated instrument that is ready for use.

People: Review committee (e.g., translators, project managers, subject matter experts)

Linguistic Validation of Clinical Outcome Assessments

With its key role in ensuring accurate and culturally appropriate translations, LV increasingly contributes to reliable data collection and meaningful research across the life, social, and behavioral sciences. In multinational clinical trials, LV validates questionnaires and assessments across different languages to ensure they maintain their intended meaning and validity.

LV is most frequently used to ensure translation quality in the context of clinical outcome assessments (COA), including electronic clinical outcome assessments (eCOA). These tools measure a patient’s symptoms, mental state, or the effects of a condition on that person’s function. International clinical trials often use them to assess concepts and determine clinical benefits. COAs can be observer, clinician, or patient-reported or may be performance-based.

Historically, the process has been primarily defined and used for patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, defined by the FDA as “a type of clinical outcome assessment that is based on a report that comes directly from the patient about the status of a patient’s health condition without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” These include rating scales, surveys, and even interviews, provided the interviewer only records the patient’s response.

PROs provide valuable information subjectively experienced and directly reported by patients and study participants regarding their quality of life, well-being, symptom severity, treatment satisfaction, etc. This data is not only crucial for research, product development, and regulatory approval but is also relevant to marketing and payer communication. Therefore, it must be entirely reliable, clear, and comparable for data extraction and statistical analysis.

When LV is used to translate and adapt health and medical questionnaires and assessments in the context of multinational clinical studies, the process helps ensure that the perspectives of patients from diverse linguistic backgrounds regarding their health, symptoms, and well-being are accurately captured.

While previous recommendations focused primarily on PROs, the ISOQUOL Translation and Cultural Adaptation Special Interest Group (TCA-SIG) recently developed recommendations for observer-reported (ObsRO), clinician-reported (ClinRO), and performance (PerfO) outcome measures that are closely aligned with the standard process for linguistic validation of PRO measures and consist of the following steps:

- Creation of a concept definition document

– Providing the conceptual basis for all items/tasks.

- Developer review of concept definition document

- Two forward translations

- Reconciliation of forward translations

- One back-translation

- Project Manager review and evaluation of back-translation

- Developer review of back-translation evaluation

- Native-speaking clinician review of the translation

- Proofreading

- Cognitive debriefing/pilot testing

Regulatory Aspects

Currently, neither the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nor the European Medicines Agency (EMA) explicitly prescribe the use of LV in clinical trials and medical product development. However, the FDA strongly encourages the use of the process in clinical trials, especially for PROs, to ensure the reliability and validity of data from diverse patient populations. Sponsors are generally required to provide evidence of the LV process, including details on translation methodology, translator qualifications, and cognitive debriefing results, as part of clinical trial submissions.

Similarly, the EMA recognizes the importance of LV in clinical trials and mandates that sponsors provide translated versions of PRO measures for multinational studies. Sponsors are expected to adhere to international standards and best practices. When submitting applications to the EMA for marketing authorization, sponsors must provide the same evidence of LV as the FDA requires.

In summary, although there is no explicit mandate, both regulatory agencies emphasize the crucial role of LV in ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and validity of PRO measures in clinical trials and expect sponsors not only to follow but also to document rigorous translation and cultural adaptation processes as part of their regulatory submissions to ensure that clinical trial data accurately reflects the perspectives and experiences of diverse patient populations.

Conclusion

When properly conducted, linguistic validation can be a powerful tool to ensure accuracy, cultural relevance, and conceptual equivalence in translating clinical trial instruments and COA measures. This process requires striking a delicate balance between accuracy, cultural adaptation, and practical considerations. If this is not achieved, the outcome could not only compromise data quality and cause issues with data analysis but ultimately undermine a study’s scientific integrity.

Given the potential impact on a large, diverse patient population, it is vital to ensure that the process is done well by qualified professionals. An experienced Language Service Provider (LSP) with LV expertise can be a valuable asset and an invaluable partner in successfully managing such projects.

These providers have experience managing large multilingual LV projects and access to well-qualified translators with the requisite subject matter expertise. This expertise becomes even more important when translation into multiple languages and/or language variants or rare languages is required, especially when dealing with complex scientific and medical content. In the second article of this series, we will delve into the pivotal role of language professionals and LSPs – and what to look for to find the right partner for your LV needs.

Learn more about Vistatec Life Sciences here.